~~~~~~~~~

The Story of Polioptics is a 10-part Web narrative based on a multi-media presentation — POLIOPTICS: Political Influence Through Imagery, From George Washington to Barack Obama — that debuted on college campuses in 2009.

Part 4 of the Story of Polioptics opened in 1976 and swung open the door to the media presidency. Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, each in their own way, ran outsider campaigns in ’76 and ’80 and won their contests riding a wave of the mere exposure effect.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush temporarily stalled that trend, becoming the first sitting vice president to win election since 1836, when Martin Van Buren succeeded Andrew Jackson. A few pivotal visual moments aided the vice president’s cause. One was this watershed sequence in the presidential debate against Governor Michael Dukakis when, in response to a provocative question from CNN’s Bernard Shaw, the governor offered a clinical response to what many husbands would consider fightin’ words.

Then there was the Bush campaign’s mocking ad of what advance people hold high as the most spectacularly failed photo op in presidential campaign history. And to put the nail in the Dukakis’s coffin, there was Willie Horton.

Once in office, however, Bush failed, with few exceptions, to match his predecessor’s mastery of the visual. I was captivated by this Diana Walker shot for Time of President Bush at Magic Hour with the troops in Kuwait — and I learned a lot about imagery from Diana during my White House years — but, beyond that, the enduring images of Bush that visualists recall today are supermarket scanners and looking at your watch.

William Jefferson Clinton then took the free media-dominated visual campaign to a new level.

Back in 1991, when his title was simply Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas, I answered an invitation from an old friend from the Dukakis campaign to attend the Clinton advance school in Little Rock. I looked at the calendar and saw that I had eight months before I was scheduled to begin business school. Why not head back on the road, see a few new parts of the country, and help out the long shot Democratic candidate? I ended up never going to business school. I ended up in the White House.

With a few initial advance trips for Clinton under my belt, I went home to Boston in early 1992 and took stock of the rote events featuring candidates of both parties that were being staged in front of blue curtains. A question kept gnawing at me: What Would Deaver Do? In a campaign whose most captivating visual was Ross Perot holding up a chart, how can you position a presidential candidate as more action-oriented?

With a few initial advance trips for Clinton under my belt, I went home to Boston in early 1992 and took stock of the rote events featuring candidates of both parties that were being staged in front of blue curtains. A question kept gnawing at me: What Would Deaver Do? In a campaign whose most captivating visual was Ross Perot holding up a chart, how can you position a presidential candidate as more action-oriented?

The California primary was the biggest prize for Democratic candidates. That summer, the America’s Cup was being staged off the coast of San Diego. What better backdrop for a man of action than the foamy surf of the Pacific Ocean surrounded by tacticians and winch grinders? With this JFK shot in mind, I faxed a note to a friend on the governor’s advance staff suggesting that Governor Clinton should go sailing with one of the America’s Cup teams. Bad idea. We have since learned that the high seas bring high risks. My note, thankfully, was ignored.

As the months passed, taking cues from those old pictures of Reagan in Time Magazine, my eye for the visual became more refined. I stayed out on the road full time for Governor Clinton, moving from coast to coast helping to produce events for the campaign on an increasingly grand scale. Channeling that iconography that had such a powerful impact on me as a boy, and carrying with me Reagan’s best moments that I had watched from my dorm room in college, my events mixed together the political ingredients of front page photos. There were colorful characters, caption-inspiring props, the sense of motion that excites editors, music that adds rhythm to an event, and lighting which accentuates the key elements. These ingredients were then baked into compelling campaign moments.

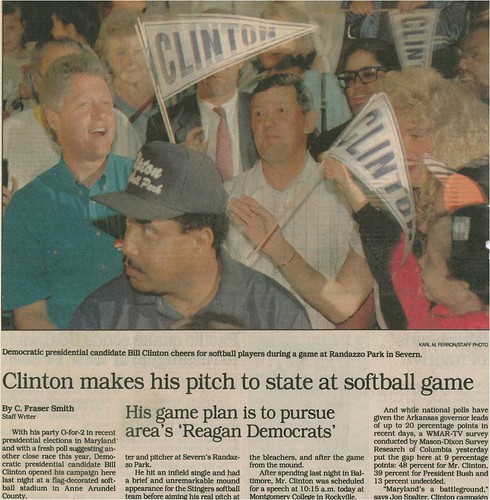

The job of a site advance man is like that of an architect designing an urban landscape. Every event should be designed down to last square the inch using a pencil, ruler and graph paper. Consider this sketch as a case in point: I was in Baltimore operating with vague instructions from Little Rock to find an event site for a late afternoon hit somewhere within 15 minutes driving distance of Baltimore-Washington International Airport. By happenstance, I drove my rental car into the parking lot of a nearly deserted baseball field called the Randazzo Softball Complex just a few miles from the BWI runway. Beyond a couple of guys playing pickup softball, the place was a blank canvas.

“Can you put together two teams?” I asked the ballplayers. I said we might be able to reach out to a screen printing shop to create some appropriate softball uniforms to finish the scene. We printed tickets, designed pennants and recruited a crowd. If you build it, they will come. What began as batting practice became an evening spectacle played out in front of 3,000 fans. The notes scratched out on ruled paper became this: a Maryland softball game instead of a rally, written up in the Washington Post oozing with metaphor.

Clinton didn’t need to make a speech. All we needed was a classic photo op – throwing out the first pitch — to capture just the right message in the stories in the next day’s newspaper.

To the annoyance of Clinton’s traveling staff, the scene proved too fun to leave at that. The governor also took a turn at the plate and they worried that it would draw analogies to Casey At The Bat: Mighty Clinton striking out. Instead, he beat out an infield single, and scored a run for the anointed “home team” — the Stingers.

Elsewhere along the 1992 campaign trail, steel towns proved ripe for visuals. Weirton, West Virginia oozed history — a town where both John and Robert Kennedy visited during their respective campaigns. Bill Clinton and his new running mate, Al Gore, would visit the town on one of their stops on their first bus tour after leaving the Democratic Convention in New York City. Wierton Steel, which has since gone bankrupt and been sold to foreign investors, was then a model for employee stock ownership and was happy to host the new ticket. But to make the picture work it helped to have their hard hats labeled.

Another bus tour took us to Central Florida, the Sunshine State’s staunchly Republican horse country. We found the Ocala Shrine Rodeo Arena unused and convinced the decision makers in Little Rock that we could fill it with a rabid throng to welcome the Democratic Ticket. They didn’t believe us, but were happy to find folks hanging from the rafters when the busses arrived.

To lend more drama to the moment, we planned to have the candidates’ tour bus roll right off the highway into the middle of the packed bowl, forming an instant backdrop for the event. It was one thing to pack a community center in Democrat-dominated West Virginia; quite another to top that in heavily Republican Florida. Waking up at our Holiday Inn the next morning, coverage in the influential St. Petersburg Times made all the effort worthwhile. Of particular note was the declarative column by local pundit Howard Troxler:

“But it was Ocala that stuck with me the most. That crowd hooted and hollered and jumped like nothing else I’ve seen, and as I sat there, the thought that I had been pushing aside for days finally fought its way out into the open: He’s going to win, isn’t he? He’s going to win Florida, and he is going to be president.”

Howard Troxler Column

St. Petersburg Times

October 7, 1992

When a politically unpredictable columnist declares, as a result of the images you created, that your Democratic candidate is going to win deep in Republican territory, it validates the days of sweat and worry that went into making it happen.

Less than a month later, the Clinton-Gore advance team road warriors gathered in Little Rock on Election Night. Campaign Scheduler Susan Thomases assembled us in an empty office building and described — in terms unbelievable at the time — how we would soon find ourselves overseas representing the President of the United States on historic state visits. As we stood there, weary from weeks of nonstop campaigning, we couldn’t wait to get our passports stamped.

In one way or another, many of us made our way to Washington to begin pursuing Susan’s promise. Persistence — and equal doses of luck and good timing — soon sent me to the White House as one of the President’s three schedulers. When a White House event lacked a visually-minded producer, I lent a hand in bringing Mike Deaver’s production values to Clinton’s White House. We were choreographing front-page moments set against one of the world’s most recognizable backdrops. In the spring of 1993, when the tragedy that inspired Blackhawk Down sped the return home of the Marines stationed in Mogadishu, we worked to suitably welcome them back to the South Lawn. It was a stage unlike any other.

My big break came in September that year when the President traveled to meet Pope John Paul II for the first time at World Youth Day in Denver. I wasn’t there, but word quickly came back of a significant advance snafu that has since become legend. A member of our staff, trying to reduce the human clutter of people wandering between “the principals” — the president and the 73-year-old pontiff — and the planned backdrop of Air Force One, yanked one of them aside, a white-robed minister, said to be the Vatican’s Secretary of State.

Advance people can become too focused on perfection. Sometimes, you just have to trust the photographers to hold their fire, let the shot clear itself out and the event to find it’s groove.

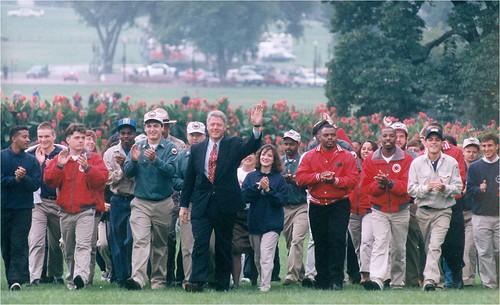

That gave me, at age 27, an opportunity to serve as the White House director of production. Every day, my job would be to help manage the event portfolio with responsibilities similar Mike Deaver in the decade before. One of the early memorable moments was the signing of legislation establishing Americorps. The plan started out as rather ordinary: erect a tent on the South Lawn; invite a crowd; usher in the press; make a speech; sign the bill with a handful of pens emblazoned with the Presidential Seal and call it a day.

But tents are hard to work in. They muffle sound, kill light and restrict maneuver. It’s damned tough to make a good picture in a tent.

Americorps

“So,” I thought, “let’s tweak it a bit.” A diagram was drawn. Some persuasion was needed. Eventually, when the president emerged from the Oval Office expecting a routine bill signing, we ushered him down South Drive, hidden from view. He took his place behind a grove of trees among a gaggle of red-jacket Americorps volunteers who would escort him up the South Lawn to the event site. Positioned 50 years away with a clear line of sight was a selected pool of photographers strategically positioned to capture “the walk up.” The band was cued. The walk began. The shutters whirred.

Here’s what made this image Page One material in the New York Times and why it is still remembered: it was a cinematic moment. George H.W. Bush rarely did events that featured physical movement. They were static, often staged in front of that ubiquitous blue drape. Instead, we looked at what Hollywood was doing — the framing of and iconic scene in Armageddon was borrowed from a similar moment in Tombstone, which was a takeoff of the beloved image of The Magnificent Seven. Lenses love motion, whether on foot or horseback – the genuine smiles on the kids faces; the clapping hands extended; the legs captured in mid-stride — and we were feeding the lenses.

- The same ideas were found in Iowa in ’93 when the Mississippi burst its banks. Going to the river to get the briefing from Governor Terry Branstad comes off as more empathetic than gving a speech behind a podium. Don’t get me wrong, you still do the speech in order to give substance to the story, but the image is what moves emotions on Page 1.

- In 1994, we staged the First Summit of the Americas in Miami (I would later return briefly to advance work to help with President Obama’s trip to the Fifth Summit of the Americas in Trinidad). This picture doesn’t tell the whole story of trying to get three dozen heads of state and government to mimic one of those old movie posters with a “group walk” up to an awaiting platform for an otherwise-static “family photo.”

- Remember those iconic pictures of the World War II allies — FDR, Churchill and Stalin — at summits in Yalta and Casablanca? In homage to those days, in the fall of 1995, we helicoptered President Clinton and his Russian counterpart, Boris Yeltsin, from New York City to FDR’s home for a summit at Hyde Park. We purposefully posed Bill and Boris with their backs to the cameras (the press was herded behind ropes to manipulate them into position to shoot only the unique angle) so that their facial features didn’t distract the viewer from equating the modern leaders with their forebears. Most major newspapers carried the same Stephan Savoia AP photo of Clinton and Yeltsin in FDR’s wicker chairs against the fall foliage and the splendor of the Hudson River Valley.

- On a historic visit to Belfast, Northern Ireland, at the end of the year, a U.S. Air Force plane flew a Tennessee Christmas tree across the Atlantic to the city center. Van Morrison provided the musical accompaniment as Clinton pulled a lever with a Catholic girl and Protestant boy to light the symbol of peace before a gathered throng. The picture played out exactly as we designed it with a pencil, ruler and graph paper, and it too was a focal point for the world’s front pages.

- Days later, in Baumholder, Germany, with U.S. troops about to become involved in the war in Bosnia, inspiration came from the early Alexander Gardner photos of Lincoln at Antietam. The soldiers of the 1st Armored Division assembled in ranks as the Commander-in-Chief and his generals, hidden from view, turned a corner and entered the parade ground in full stride, walking headlong into a small pool of photographers positioned to capture the entrance. The result: two rare “double truck” photos as the lead stories in Time and Newsweek. The picture made the message.

- A few weeks later, now into January of President Clinton’s reelection year, we again joined U.S. soldiers participating as part of the NATO Implementation Force, or IFOR, this time in their encampment in Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina. The wrinkle here – to the chagrin of the Secret Service, which would have happily driven the president to the back of the event site in a heavily armored vehicle — was to take advantage of the geometry of the “cutaway” press position. From a slightly elevated platform, they captured the President—escorted by General William Nash—entering from the front of the event site directly through a cordon of saluting troops.

- The remainder of the year was largely devoted to the reelection campaign. The campaign’s theme, like Reagan’s 1984 “Morning in America,” was built on a poll-tested metaphor: “Building a Bridge to the 21stCentury.” Even our “21stCentury Express” whistle-stop train tour that carried Clinton from Huntington, West Virginia through the rust belt states of Kentucky, Ohio, Michigan and Indiana, on his way to the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago, Illinois, echoed Reagan’s trip 12 years before. Bill Clinton and his second term team would provide that bridge to a new millennium. The speeches, talking points and, yes, the design of the events themselves, were centered around that phrase and other heavily-researched reinforcing nuggets of language, like “Meeting America’s Challenges” and “Protecting America’s Values.”

- Looking at a typical event image in the newspaper or the evening news, you didn’t have to read the whole story or listen to the full evening news report to have the message sink in. In a single glance, viewers caught the President, his campaign metaphor and the easily read nugget on information, conveying the whole story without a single line of text from the actual story.

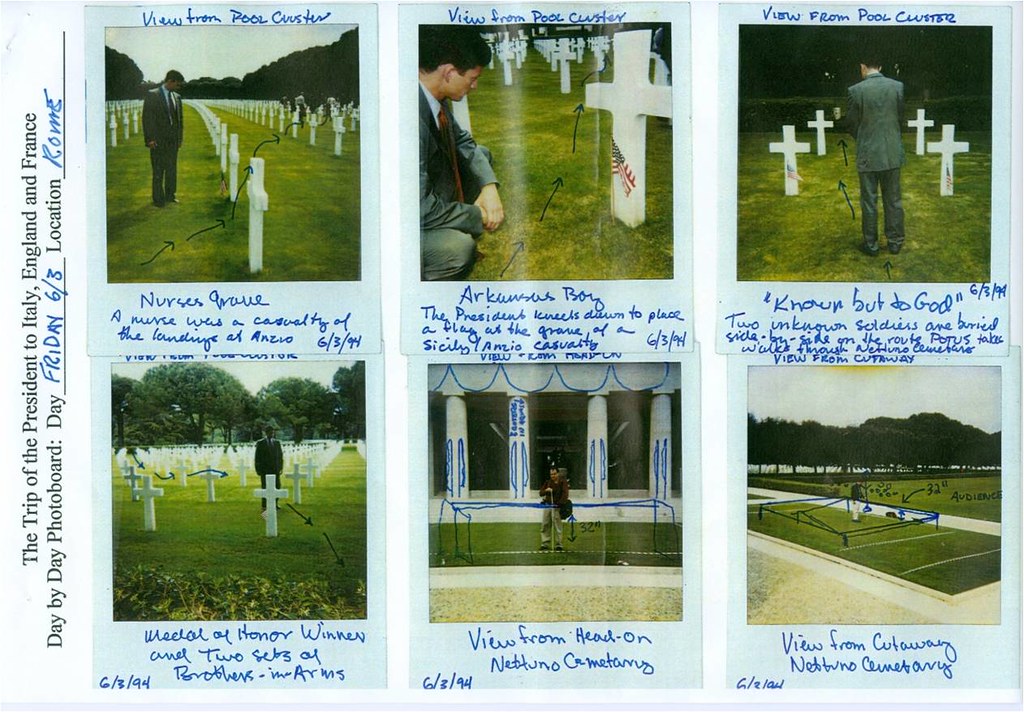

My most-cherished project – the 50th Anniversary of D-Day in 1994 – was also my biggest screw-up.

A story board from Normandy

We went to Europe twice on White House “pre-advance” trips to story-board how the images might play out in the press. We studied archival footage of Ronald Reagan’s 1984 visit to commemorate the 40th Anniversary, site of the emblematic “Boys of Point du Hoc” speech that made Peggy Noonan famous. I remembered, and greatly admired, news magazine photos of Ron and Nancy in a seemingly private moment visiting the graves of fallen soldiers. At Nettuno Cemetery in Italy, for example, we worked with the wire photographers to give them special access to pre-planned stops on the president’s route through the soldier’s final resting place. They used that access to stage remote-fired cameras to capture the visit from new angles.

But while much of the visit to Normandy would echo Reagan’s from a decade earlier, we decided to do something Reagan never did: visit Omaha Beach itself.

Clinton couldn’t do it alone—that would not adequately tell the story of the veterans’ sacrifice. So we researched the archives of D-Day Medal of Honor recipients like Bob Slaughter who planned to make the return trip to France, and we selected three veterans still sprightly enough to accompany Clinton for a long walk down a winding path to Omaha where they would say a prayer for fallen comrades. We storyboarded that walk, too.

The Secret Service, understandably, expressed reservations about the idea; after all, the walk would end at the water’s edge beneath the high ground that five decades before offered an advantageous position to repel the invading allies. The contours of the coastline hadn’t changed in 50 years, and the same high ground was a headache to neutralize with counter-sniper teams. But we worked it out – spotting the planned prayer in an area that could be safely protected.

Then, a last minute curve ball. A senior member of the White House staff cut a deal with Newsweek for Pulitzer-winning photographer Eddie Adams – memory can’t erase these shots of his from the Vietnam War – to have a private, exclusive photo opportunity to cover Clinton on the beach.

The Secret Service doesn’t like curve balls, especially on a wide open beach. The agent assigned to work with me insisted we take steps to insure that the president not venture further onto the beach out of the secure area. To mark a boundary that the president could easily see, I found a field of large rocks that separated the fine Omaha Beach sand from the tall grass that led up to the National Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. Over the course of five sweaty minutes, I ferried a small pile of those rocks about 30 feet onto the beach.

When the president approached with his accompanying veterans, I pulled him aside and told him about the curve-ball we were thrown and cautioned him to stay on our side of the improvised rock pile to assure his safety. He said okay and rejoined the decorated vets.

When the president approached with his accompanying veterans, I pulled him aside and told him about the curve-ball we were thrown and cautioned him to stay on our side of the improvised rock pile to assure his safety. He said okay and rejoined the decorated vets.

The prayer happened as planned. It was a soulful, genuine moment. Photos that quickly moved on the wire, and in the world press, reflected that. I thought — with some satisfaction — that we put our own imprint on commemorating D-Day, breaking out of the famous Reagan mold and offering a memorable moment that would fill veterans unable to make the trip with much deserved pride.

Unfortunately, we weren’t done. The veterans were ushered back to my position near the grass out of camera range. Adams moved in. But he had lost a step since Vietnam. Minutes passed as he changed lenses and adjusted his position. Clinton, lacking much else to do on the beach, killed time waiting for Adams. Eventually, he wandered over to our stone pile and, ad libbing our script, squatted in front of them. He fashioned the 20 or so rocks placed as a boundary marker into the shape of a cross, just like the 9,000 American crosses at the cemetery high above us.

This simple act — the emotional coda to several days worth or heart-wrenching remembrance – was the equivalent of giving a year’s worth of material to Rush Limbaugh. Loaded with ammo, the talk show host roared into action and thrust his criticism onto the airwaves. I haven’t listened to Rush in a while, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he still talks about it. To this I can attest: when Barack Obama recently visited the Louisiana coastline to see for himself the tar balls from the BP oil spill that washed up on the beach, I received a number of snarky emails that compared the new president’s photo op with my 1994 folly (it’s interesting, by the way, the convenient cropping that went on with the Obama scene).

It’s fair to argue about the genuineness of what was, frankly, a scrupulously planned set of events. But in the modern presidency, with a press corps that demands access, is there any choice but to plan? The alternative—and I can attest to this, too, from many unplanned presidential moments in my experience—is media mayhem. Our objective in going to Normandy—part of any president’s job—was to honor the sacrifice of our veterans and show them a country’s gratitude. The compositions are largely interchangeable. The task is the same, no matter if the advance people are representing President Reagan, Clinton, Bush or Obama. We are telling a story. Sometimes it is sad; sometimes it is uplifting. In the 1990′s, the lenses of the traveling press corps were our only immediate conduits to people back home. In fairness to Clinton, he hadn’t a clue the rocks would be there. He reacted as many might as a photographer fumbled for his lens and delayed a shoot, reflecting on many days spent amid thousands of crosses. He made one of his own.

My error—knowing how any action taking place in front of a lens can be misconstrued—was veering from the planned script.

In June 2009, Barack Obama continued the long tradition of U.S. Presidents paying homage to veterans at Normandy. As we read the stories of veterans who return or are no longer there, it’s always a moving moment. As fewer remain of the Greatest Generation each day, the process of honoring them in person is coming to an end. I only wish, with Clinton’s visit, I hadn’t allowed a photo too far.

~~~~~~~~~~

If you missed earlier parts of the the Story of Polioptics, begin at the beginning with Polioptics Part 1 and Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4.

And then continue reading The Story of Polioptics. Additional parts of the narrative will appear every few days. When it’s complete, it will be archived it its own section of www.Polioptics.com.

Stay tuned for upcoming posts:

Part 6: The 21st Century Presidency

Part 7: The Internet, Pop Culture and the Rise of Obama

Part 8: The First 100 Days…And the Next Thousand

Part 9: Port of Spain

Part 10: Homage to Image

Leave a Reply